Thoracic surgeons frequently encounter closed pneumothorax cases, each serving as a reminder of the delicate balance within the chest cavity and the remarkable resilience of the human body. While potentially serious, this condition often presents subtly in its initial stages. Consequently, awareness and prompt recognition are crucial for patients and healthcare providers to ensure timely and appropriate intervention. The subtle nature of early symptoms highlights the importance of vigilance and thorough assessment in thoracic medicine.

Understanding Closed Pneumothorax

Closed pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space between the lung and chest wall without an apparent external wound. Unlike its counterpart, open pneumothorax, there’s no visible chest wall defect. This makes closed pneumothorax a more insidious condition, and often challenging to diagnose.

The pleural space normally contains a small amount of fluid, allowing the lungs to move smoothly during respiration. Air entering this space disrupts the negative pressure that keeps the lungs expanding. This small change in pressure can have major effects, potentially leading to partial or complete lung collapse.

Understanding the causes of closed pneumothorax is crucial for effective management and prevention. In my clinical experience, the most common causes include:

- Spontaneous Pneumothorax: Often seen in young, tall, thin individuals, particularly males. It’s typically caused by the rupture of small air-filled sacs (blebs) on the lung surface. We call it spontaneous because it isn’t triggered by external circumstances, making it manifest randomly.

- Traumatic Pneumothorax: Resulting from blunt chest trauma, such as from motor vehicle accidents or falls. The impact can cause lung tissue to tear without breaking the chest wall. The injury’s severity and nature can lead to either open or closed traumatic pneumothorax, depending on whether the chest wall is penetrated, allowing air in, or the chest wall remains intact.

- Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax: In patients with underlying lung diseases such as COPD, cystic fibrosis, or certain interstitial lung diseases. We call this ‘secondary pneumothorax’ because it results from a separate condition rather than the primary one.

Each aetiology presents its challenges in management and long-term care planning.

Subtle Signs and Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of closed pneumothorax can vary widely, from subtle signs to severe respiratory distress. Common closed pneumothorax symptoms include sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, a dry, non-productive cough, and tachycardia, where the heart rate goes over 100 BPM without apparent cause. That is because the pneumothorax can affect the oxygen levels in the blood, affecting lung function. In severe cases, it can lead to cyanosis, where the nails turn blue due to lack of oxygen or hypoxemia, where oxygen levels in the blood are below normal.

Importantly, the severity of symptoms doesn’t always correlate with the size of the pneumothorax. Some patients present minimal symptoms despite large pneumothoraces. In contrast, others experience significant distress from small air pockets.

Diagnostic Approach

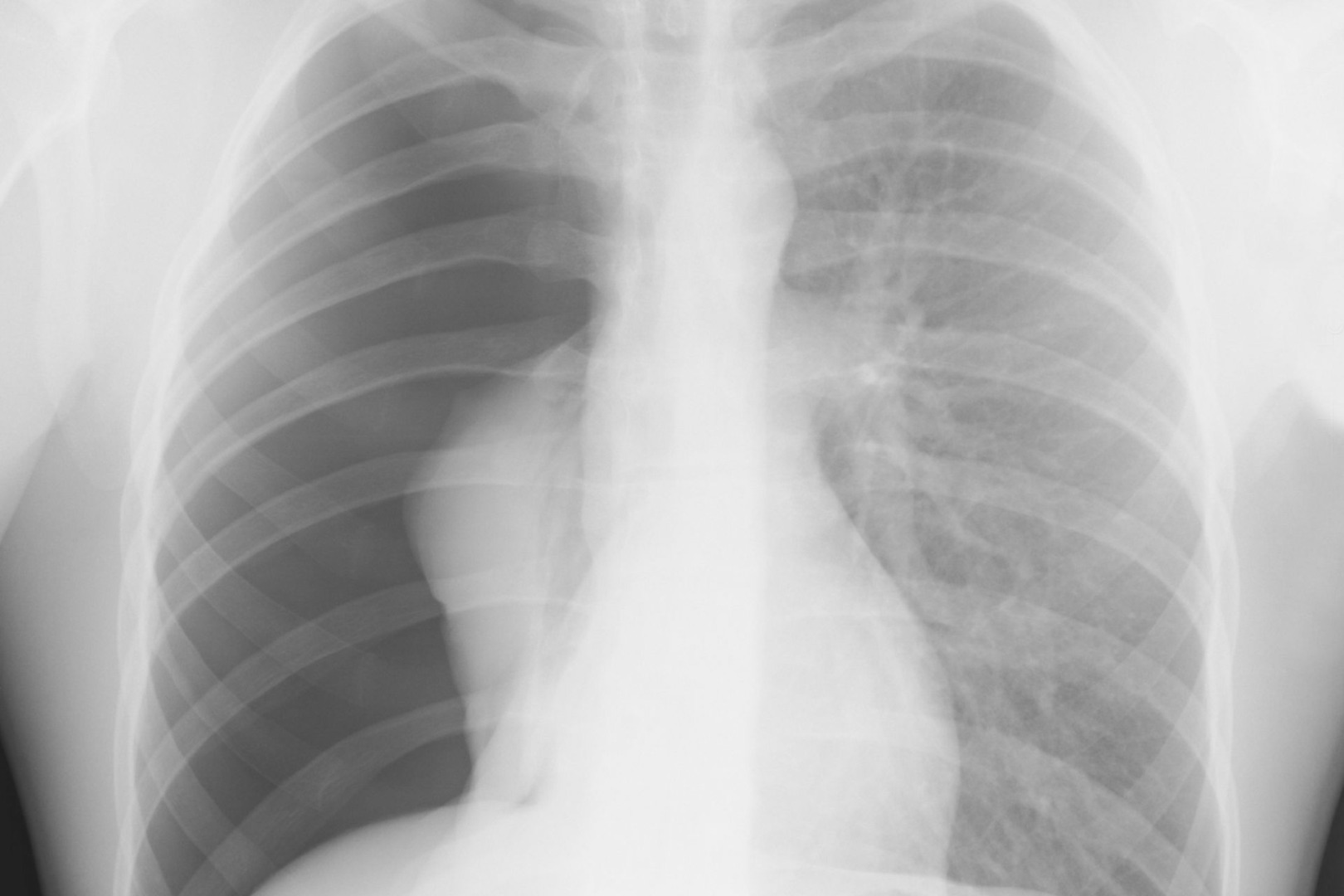

Diagnosing closed pneumothorax requires a combination of clinical acumen and appropriate imaging studies. The process typically involves a thorough history and physical examination, paying close attention to risk factors and subtle clinical signs.

Chest radiography remains the primary source of diagnosis, revealing the presence of pleural air and the degree of lung collapse. This is the best way to determine if the chest wall has been penetrated, determining whether this is a closed or open pneumothorax.

Computed tomography (CT) is particularly useful in cases where X-rays are inconclusive or when evaluating underlying lung pathology. Ultrasound has emerged as a valuable tool for rapid assessment, especially in emergency settings.

Treatment Strategies from Conservative Management to Surgical Intervention

Closed pneumothorax treatment has evolved significantly, with approaches tailored to the patient’s condition and overall health status. Treatment options range from observation for small, asymptomatic pneumothoraces to oxygen therapy for accelerating reabsorption of pleural air, needle aspiration for symptomatic patients or larger air collections, and chest tube insertion for significant pneumothoraces. Pleurodesis may be considered for recurrent cases to prevent future collapses.

One of the most significant advancements in thoracic surgery for managing closed or open pneumothorax is Uniportal Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (U-VATS). This minimally invasive technique allows for intricate chest procedures through a single, small incision, offering advantages such as minimal postoperative pain, faster recovery times, excellent cosmetic results, and enhanced visualisation of the thoracic cavity.

U-VATS has proven particularly valuable for the precise identification and treatment of air leaks, resection of blebs or bullae, mechanical pleurodesis, and management of complicated cases with adhesions or loculated pneumothorax.

Long-term management of closed pneumothorax extends beyond the acute phase. It involves follow-up imaging to ensure complete recovery and monitor for recurrence. It also entails lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation and avoidance of activities that dramatically change ambient pressure, like scuba diving, patient education to recognise symptoms of recurrence, and genetic counselling in cases with a family history of spontaneous pneumothorax.

This comprehensive approach to long-term care is crucial in preventing recurrence and ensuring optimal patient outcomes.

Closed pneumothorax, though a significant medical concern, has become increasingly manageable with advancements in diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities. The role of thoracic surgeons has evolved to encompass surgical expertise, patient education, and long-term care management. This comprehensive approach allows for better outcomes and empowers patients to participate actively in their respiratory health.